Note

Go to the end to download the full example code. or to run this example in your browser via Binder

SDE simulation: creating synthetic datasets using SDEs#

This example shows how to use numeric SDE solvers to simulate solutions of Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs).

# Author: Pablo Soto Martín

# License: MIT

# sphinx_gallery_thumbnail_number = 2

SDEs represent a fundamental mathematical framework for modelling systems subject to both deterministic and random influences. They are a generalisation of ordinary differential equations, in which a diffusion or stochastic term is added. They are a great way of modelling phenomena with uncertain factors and are widely used in many scientific areas such us financial mathematics, quantum mechanics, engeneering, etc.

Mathematically, we can represent an SDE with the following formula:

where \(\mathbf{X}\) is the vector-valued random variable we want to compute. The term \(\mathbf{F}\) is called the drift of the process, and the term \(\mathbf{G}\) the diffusion. The diffusion is a matrix which is multiplied by the vector \(\mathbf{W}(t)\), which represents a Wiener process.

To simulate SDEs practically, there exist various numerical integrators that approximate the solution with different degrees of precision. scikit-fda implements two of them: Euler-Maruyama and Milstein In this example we will use the Euler-Maruyama scheme due to its simplicity. However, the results can be reproduced also using Milstein scheme.

The example is divided into two parts:

In the first part a simulation of trajectories is made.

In the second part, the marginal probability flow of a stochastic process is visualized.

Simulation of trajectories of an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process#

Using numeric SDE solvers we can simulate the evolution of a stochastic process. One common SDE found in the literature is the Ornstein Uhlenbeck process (OU). The OU process is particularly useful for modelling phenomena where a system tends to return to a central value or equilibrium point over time, exhibiting a form of stochastic stability. In this case, the process can be modelled with the equation:

where \(\mathbf{W}\) is the Brownian motion. The parameter \(\mu\) represents the equilibrium point of the process, \(\mathbf{A}\) represents the rate at which the process reverts to the mean and \(\mathbf{B}\) represents the volatility of the processs.

To illustrate the example, we will define some concrete values for the parameters:

from typing import Any

import numpy as np

NDArrayFloat = np.typing.NDArray[np.floating[Any]]

A = 1

mu = 3

B = 0.5

def ou_drift(

t: float,

x: NDArrayFloat,

) -> NDArrayFloat:

"""Drift of the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process."""

return -A * (x - mu)

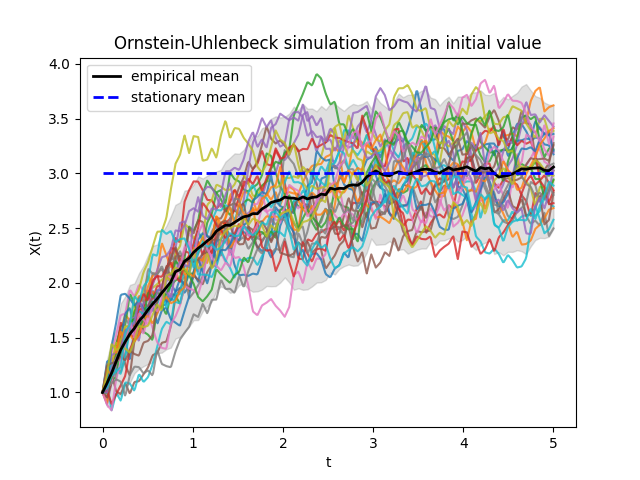

For the first example, we will consider that all samples start from the same

initial state \(X_0\). We can simulate the trajectories using the

Euler - Maruyama method. The trajectories of the SDE calculated by

skfda.datasets.make_sde_trajectories() are stored in an FDataGrid.

Then, we can plot them using scikit-fda integrated functional data plots.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from skfda.datasets import make_sde_trajectories

X_0 = 1.0

fd_ou = make_sde_trajectories(

initial_condition=X_0,

n_samples=30,

drift=ou_drift,

diffusion=B,

start=0.0,

stop=5.0,

random_state=np.random.RandomState(1),

)

grid_points = fd_ou.grid_points[0]

fig = fd_ou.plot(alpha=0.8)

ax = fig.axes[0]

mean_ou = np.mean(fd_ou.data_matrix, axis=0)[:, 0]

std_ou = np.std(fd_ou.data_matrix, axis=0)[:, 0]

ax.fill_between(

grid_points,

mean_ou + 2 * std_ou,

mean_ou - 2 * std_ou,

alpha=0.25,

color="gray",

)

ax.plot(

grid_points,

mean_ou,

linewidth=2,

color="k",

label="empirical mean",

)

ax.plot(

grid_points,

mu * np.ones_like(grid_points),

linewidth=2,

label="stationary mean",

color="b",

linestyle="dashed",

)

ax.set_xlabel("t")

ax.set_ylabel("X(t)")

ax.set_title("Ornstein-Uhlenbeck simulation from an initial value")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

In the previous image we can observe 30 simulated trajectories. We can see how the empirical mean approaches the theoretical stationary mean of the process.

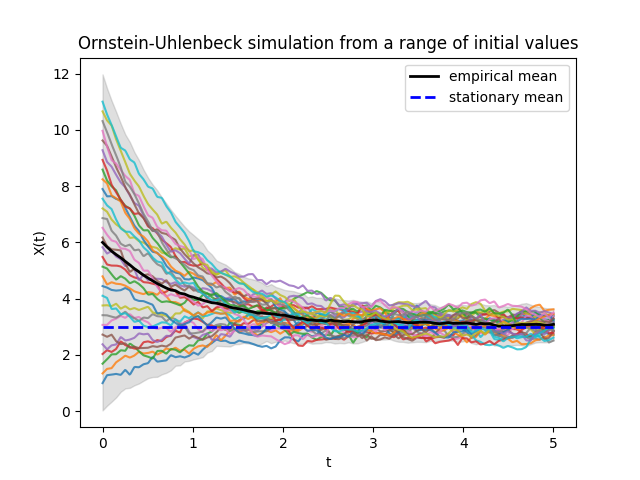

The initial point \(X_0\) from which we compute the simulation does not need to be always the same value. In the following code, we compute trajectories for the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process for a range of initial points.

X_0 = np.linspace(1, 11, 30)

fd_ou = make_sde_trajectories(

initial_condition=X_0,

drift=ou_drift,

diffusion=B,

start=0.0,

stop=5.0,

random_state=np.random.RandomState(1),

)

grid_points = fd_ou.grid_points[0]

fig = fd_ou.plot(alpha=0.8)

ax = fig.axes[0]

mean_ou = np.mean(fd_ou.data_matrix, axis=0)[:, 0]

std_ou = np.std(fd_ou.data_matrix, axis=0)[:, 0]

ax.fill_between(

grid_points,

mean_ou + 2 * std_ou,

mean_ou - 2 * std_ou,

alpha=0.25,

color="gray",

)

ax.plot(

grid_points,

mean_ou,

linewidth=2,

color="k",

label="empirical mean",

)

ax.plot(

grid_points,

mu * np.ones_like(grid_points),

linewidth=2,

label="stationary mean",

color="b",

linestyle="dashed",

)

ax.set_xlabel("t")

ax.set_ylabel("X(t)")

ax.set_title("Ornstein-Uhlenbeck simulation from a range of initial values")

ax.legend()

plt.show()

In the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process, regardless the initial value, the trajectories tend towards the stationary distribution.

Probability flow#

In this section we exemplify how to visualize the evolution of the marginal probability density, i.e. probability flow, of a stochastic differential equation. At a given time t, the solution of an SDE is not a real-valued vector; it is a random variable. Numeric integrators allow us to generate trajectories which represent samples of these random variables at a given time t. Probability flow is a very interesting characteristic to study when simulating SDE, as it gives us the possibility to visualiaze the probability distribution of the solution of the SDE at a given time. We will present a 1-dimensional and a 2-dimensional example.

In the first example, we will analyse the evolution of the Ornstein Uhlenbeck process defined above where all the trajectories start on the same value \(X_0\) (the initial distribution is a Dirac delta on \(X_0\)). The solution of the OU process is theoretically known, so we can compare it with the empirical data we get from numeric SDE integrators.

The theoretical marginal probability density of the process is given in the following function:

from scipy.stats import norm

def theoretical_pdf(

t: float,

x: NDArrayFloat,

x_0: float = 0,

) -> NDArrayFloat:

"""Theoretical marginal pdf of an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process."""

mean = x_0 * np.exp(-A * t) + mu * (1 - np.exp(-A * t))

std = B * np.sqrt((1 - np.exp(-2 * A * t)) / (2 * A))

return norm.pdf(x, mean, std)

In this case we will simulate a big number of trajectories, so that we get better precision.

X_0 = 0.0

t_0 = 0.0

t_n = 3.0

fd = make_sde_trajectories(

initial_condition=X_0,

n_samples=5000,

drift=ou_drift,

diffusion=B,

start=t_0,

stop=t_n,

random_state=np.random.RandomState(1),

)

We create an animation that compares the theoretical marginal density with a normalized histogram with the empirical data.

from matplotlib import rc

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

x_min, x_max = min(X_0 - 1, mu - 2 * B), max(X_0 + 1, mu + 2 * B)

x_range = np.linspace(x_min, x_max, 200)

epsilon_t = 1.0e-10 # Avoids evaluating singular pdf at t_0

times = np.linspace(t_0 + epsilon_t, t_n, 100)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(7, 10))

rc("animation", html="jshtml")

# Creation of the plot.

ax_trajectories = axes[0]

ax_distribution = axes[1]

ax_distribution.set_xlim(x_min, x_max)

ax_distribution.set_ylim(0, 4)

ax_distribution.set_xlabel("x")

ax_distribution.set_title("Distribution of X(t) = x | X(0) = 0")

ax_trajectories.set_xlim(t_0, t_n)

ax_trajectories.set_ylim(x_min, x_max)

lines_0 = ax_trajectories.plot(times[:1], fd.data_matrix[:30, :1, 0].T)

ax_trajectories.set_title(

f"Ornstein Uhlenbeck evolution at time {round(times[0], 2)}",

)

ax_trajectories.set_xlabel("t")

ax_trajectories.set_ylabel("X(t)")

curve = ax_distribution.plot(

x_range,

theoretical_pdf(times[0], x_range),

linewidth=4,

label="Theoretical pdf",

color="C1",

)

hist = None

def update(frame: int) -> None:

"""Creation of each frame of the animation."""

global hist

for i, line in enumerate(lines_0):

line.set_data(times[:frame], fd.data_matrix[i, :frame, 0].T)

ax.set_title(

f"Ornstein Uhlenbeck evolution at time {round(times[frame], 2)}",

)

if hist:

hist.remove()

_, _, hist = ax_distribution.hist(

fd.data_matrix[:, frame],

bins=30,

density=True,

label="Empirical pdf",

color="C0",

)

curve[0].set_data(x_range, theoretical_pdf(times[frame], x_range))

ax_distribution.legend()

anim = FuncAnimation(fig, update, frames=range(100))

plt.close()

anim